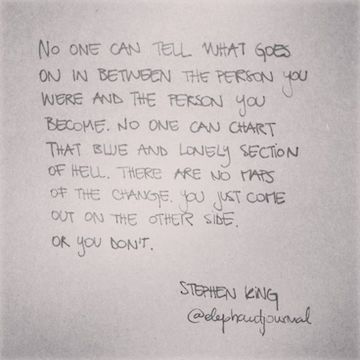

Today is my 11th “birthday,” as it’s referred to in AA – it’s the 11th anniversary of my choice to be sober and not drink again (or at least, in the beginning, for 24 hours. Baby steps.) Some people would see it as the anniversary of the absolute worst day of their lives, because for everyone, sobriety is prefaced by the concept of “rock bottom.” Everyone’s rock bottom is different in the details, but ultimately in terms of the larger picture, everyone’s is exactly the same: something terrible happened, as a direct result of their relationship with alcohol, and that something was terrible enough that the choices were few – get sober or die. My details aren’t important here (sneaky way of saying no way in hell am I relating my rock bottom story on the internet) but what is important is how I see and understand those details. Like I said, they are exactly the same as every other sobriety narrative, in that I had a choice I didn’t see as a choice but as an escape hatch.

Choosing sobriety was not really terribly difficult at the time – the knowledge that there was a problem with alcohol for me had been pretty plain for some time. I just hadn’t had the internal fortitude to address it up front and with the tools that it required. We can view sobriety, or dealing with any really scary life change, in terms of the bad. Or, if we’re smart and lucky, we can deal with it in terms of what we gain.

I have long seen my inability to finish my Ph.D. as a failure on my part. I realized, during my run with Straxi yesterday, that it wasn’t failure at all. I got a second Master’s degree during the most challenging and terrible time of my life. All these years, I’ve seen a second Master’s as a failure. Both the realization of the factuality of this as well as the realization of my own twisted thinking about it made me stop dead in my tracks on the trail. As Straxi was looking for tasty grass to eat along the sides of the trail, she didn’t really notice this, but I’m sure I looked like a light had gone off behind my eyes. Why had this taken me so long to spot?

I’ve always been sort of a pessimist about things – I’ve always figured that if I adopt the most negative way of seeing the situation, and then something better happens, I get to be relieved, instead of disappointed. I took that stance with regard to my son’s probable deployment when he was in the military, and found reassurance in planning for how I would deal with any injuries he might sustain in the war. I couldn’t get myself to truly plan for what would happen if he were to die in Iraq, but I could indeed research and plan for how to deal with the immediate aftermath of a serious injury (researching flights to Germany, for instance, which is where they took the injured soldiers and researching how to get a passport were my first two tasks).

I suppose that this way of thinking bit me in the ass, though, because always seeing the negative wasn’t a bit helpful in this situation. Granted, I didn’t get the Ph.D. I had sought and hoped for, but then again, that desire for a Ph.D. wasn’t my desire anyway – it came about as a result of what other people wanted…for me and for themselves. When I consider the track that led me to graduate school, failure to get a Ph.D. wasn’t so surprising. I always figured I would just go to school until someone approached me and told me there had been a mistake, and I should gather my things. I just drifted into the decision to go to grad school, really, and had no overwhelming urge to be a teacher. I just wanted other people to be happy.

Making decisions based on what other people want is a great way to wind up unfulfilled, lonely, and depressed. A friend of mine (I follow him on Twitter) is applying for tenure right now – we studied together, and as Cheryl Glenn said, I consider him a littermate. He probably doesn’t see me that way, but I follow him from afar and am happy when I see his successes, just like with all the other people I went to school with. I can’t imagine completing the tenure process, but then again, I couldn’t imagine writing a dissertation or passing my exams (neither of which I did). I couldn’t imagine writing a thesis, though, but I did manage that.

I can’t say that I’m glad I failed to get a Ph.D., but I can say that I can see it now as the success it was: I got a degree in the worst time of my life that allows me to do what I love. I get to teach and I even get to remember doing it the next day, which is a lot more than I can say for most of the days of grad school.

Failure, hitting bottom, feeling angry or sad or furious…depending on your placement in life, and how you’re looking at things, can actually be positives. I work every day to make sure that the lessons I got during that time aren’t forgotten. I don’t mind so much that I’ll never have tenure. I do mind terribly that I missed so much of my own life. I don’t plan to miss any more.