I first heard that term when Chris was in the military, and it was obvious he was going to be going to Iraq (he never went, fortunately, because even during a time of active warfare, my son can screw up his employment opportunities with the government). I couldn’t figure out why I felt so calmly sad, and I couldn’t quit praying and worrying. It was all very strange, and very hard, and so scary.

I ran across the term “anticipatory grief” in some of the reading I did for either my thesis (because to really put a cap on my brilliance at the time, my incredible, alcoholic unseeingness, I decided it would be a stellar idea to write about Cindy Sheehan’s dead son, and how her activism and her motherhood worked together) or just because I voraciously read every slip of information I could find about soldiers, and the war and family at home.

Cindy SheehanI took a trip to Camp Casey with a friend during grad school, as I was planning my thesis, with the hopes that I could interview Sheehan (this obviously never happened, and to be honest, I was just as glad it didn’t because I was terrified – it was like maybe the death of her son would waft over to me like a germ or something. Also, I doubted my own ability to interview her successfully). I took a bunch of photos (this was before we really had cameras on our phones, before iPhones, before much social media) while I was there, that have since been lost to the god of bits and bytes.

That war was (is?) still so incredibly hypocritical and wrong to me, and I do still believe that Dick Cheney and Bush should, along with Rumsfeld, wind up tarred and feathered at the least – definitely arrested for war crimes. I was livid at the time, terrified, worried – all those really awful emotions nobody should have to feel, ever.

I was scared, also, when the first Iraq war started – that was somehow stranger to me, in retrospect. I was still very young (I just realized I was roughly the age my son was during the second Iraq war – maybe a bit older, but not much) and the thought of the nation going to war was scary but also (I’m embarrassed to say) sort of exciting. I had spent time as an Army wife when my son was an infant (he was born in an Army hospital) and the BDUs my then-husband wore were still the jungle fatigues that were used in Vietnam (I think it says so much that the uniforms are sandy now – I guess the jungle areas should be relieved by this – we aren’t going to be bringing democracy to them at the end of a rifle any time soon, huh?).

My understanding of war (keep in mind, this was before I had had one single college level history class, and the high school history classes I had were…hmmm. They seem to have exited the building of my brain, if they were ever there to begin with) was centered around World War II. I conveniently forgot (read: was never really taught) Vietnam and I pictured the coming war to be more Victory garden than sandy hellscape.

I remember going with my work mates into the conference room (I worked for a very successful solo practitioner in Charlotte, at the time, with a fairly small office, but even it had a TV) and we watched the network news talk about troop movements – Dan Rather was not as reassuring as he later became, but maybe I just had to grow into his reporting. Who knows?

The long and short of it is that during that first run up to war, I expected us, those of us at home, whether we had family in the military or not, to make sacrifices and do things on our end to support the effort.

How quaint of me.

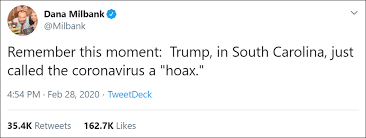

I have a similar feeling about what’s going on now – it’s not a war, technically, although we are trying to stop an invading army, so I guess we could call it a war, and most likely, if there’s money to be made from it, Fuckface Von Clownstick will indeed declare it so. But regardless of what we call it, people are generally staying home, not going out and mingling (with a few notorious and disgusting exceptions) and doing what’s recommended by doctors because it’s good for those at risk in this situation. Of course, there’s also the less altruistic twist here – people are staying home because they themselves don’t want to get sick. I can get behind both of those concepts.

But that doesn’t fully inform the low-grade worry and sadness I feel, and that sadness feels very similar to what I felt when I first was reading up on anticipatory grief. So when I ran across this article and started reading it, things really clicked for me.

There are a number of things the article suggests we do to combat this unpleasantness: find balance in the things you’re thinking, come into the present, let go of what you can’t control, and stock up on compassion. When you are faced with a change to your life, one that’s terrible beyond your reckoning, something that alters your dreams or bulldozes your internal landscape, it brings grief. You have to grieve for the marriage that’s dying, or for the degree you didn’t get, or for the life you planned but just didn’t get to lead.

Having a name for what ailed me during those dark days of wondering if my son would die similarly to Casey Sheehan and all the other young people we ultimately lost was a relief. Naming something gives you power, it allows you to see it more clearly and thus, you are more able to vanquish it or wrestle it into submission. Things won’t be the same after this corona virus experience, in many ways. I will never have a lack of toilet paper in my home again. I won’t disregard the joy inherent in grabbing my keys and just getting into the car without a plan. And, of course, many multitudes of people will be gone from the planet who shouldn’t be.

I hope we can change some things in a good way, for everyone, as a result of this.